Music

Heinz Moehn composed at least forty-eight works (forty-four of which are preserved in manuscript in a private collection held by his family), encompassing choral works, German art songs, solo and chamber instrumental works, stage music, and orchestral works. For a complete list of Heinz Moehn’s known compositions, see the catalogue, and for an understanding of the role that composition played in his musical life, see Moehn & Music. For this project, the research team collaborated to produce recordings of Moehn’s compositions in a variety of musical styles and genres, and from various periods of his life. None of these pieces have been previously recorded or published and, aside from Musik für Violine und Orchester, there are no known records of public performance of these works (however, several of Moehn’s other orchestral, choral, and stage works were performed publicly). With the exception of the score for Moehn’s Musik für Violine und Orchester, which was prepared from the manuscript by composer Paul Suchan, all performing editions were created for this project by Amanda Lalonde and Kennedy Kosheluk, with additional proof-reading assistance by Connor Elias and the performers. All recordings were made by Wayne Giesbrecht in Convocation Hall, University of Saskatchewan.

Drei Lieder nach Gedichten von Henriette Brey / Three Songs on Poems by Henriette Brey (1928)

Performed by Kate Nachilobe (soprano) and Shawn Vereschagin (piano)

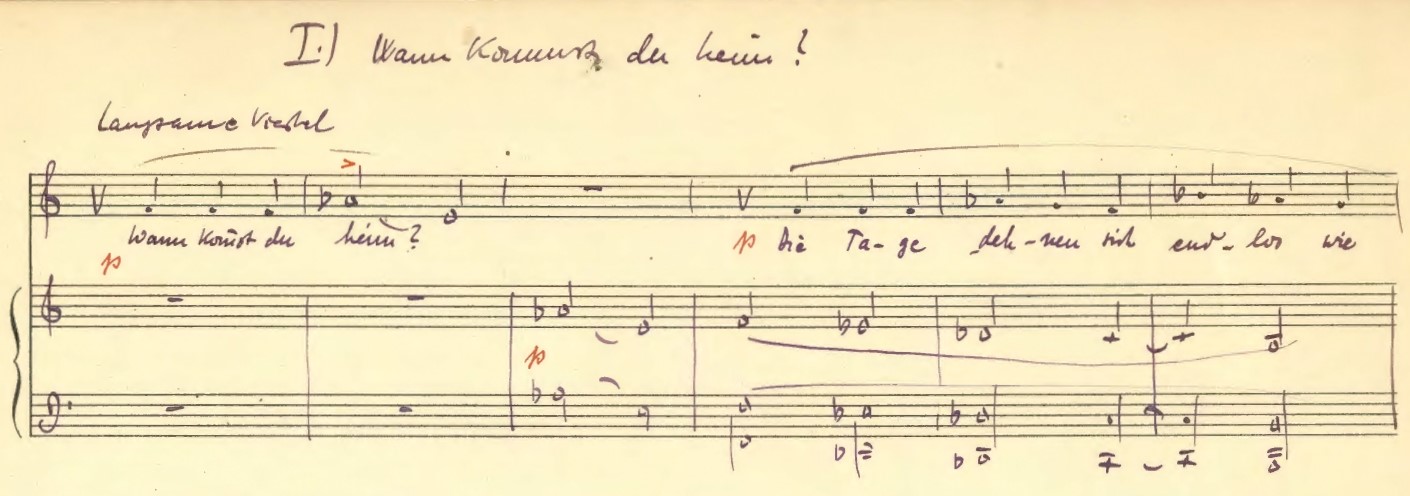

I: “Wann Kömmst Du Heim?”

II: “Trüber Tag”

III: “Erlöser Abend”

Shawn Vereschagin and Kate Nachilobe record Drei Lieder nach Gedichten von Henriette Brey in Convocation Hall, University of Saskatchewan.

Photograph by Al Ramsay.

This miniature song cycle is one of Heinz Moehn’s early compositions, and sets texts by Henriette Brey (1875-1953). Brey was a writer of poetry and prose that often dealt with religious subject matter, but these poems are more intimate and personal in tone. The three poems form a loose narrative of waiting for a loved one to come home, more waiting as day turns to night, and finally, being furious at the loved one for coming home and having caused so much anxiety throughout the day. Brey was active as a writer at the time of the composition of these songs, and some of the poems featured appear in her collection Zwischen zwei Welten: Ein Leben in Liedern, first published by Hermann Rauch in Wiesbaden in 1914, with a second edition in 1925.

Detail from the manuscript of "Wann kömmst du Heim?" from Drei Lieder nach Gedichten von Henriette Brey

In the vein of expressionism, the song settings seem to magnify the inner reality of the poems’ protagonist, rendering the everyday dramas suggested by the texts significant. For pianist Shawn Vereschagin, the harmonic language of the songs is “in the […] mould of Schoenberg and other early twentieth-century composers,” although there are “still some remnants of tonality, but a very, very small amount of that.” Soprano Kate Nachilobe also hears reminiscences of Schoenberg in some of the highly disjunct segments of the vocal line, which recall Sprechstimme. Often, these appear as angular or accented cries of pain or frustration, but the songs are perhaps not without touches of subtle humour – the third song, “Erlöser Abend,” features melodramatic vocal glissandi that may be reminiscent of yawning. In addition, the songs play with perceptions of time. Metrical irregularity is particularly pronounced in the first and second songs, contributing to the sense that the passage of time is emotionally fraught. In “Wann kömmst du Heim?” Kate Nachilobe remarks that “it feels almost as if the phrases […] meld into each other. There’s no clear stopping point for the first half of that piece,” which emphasises the protagonist’s feeling of ceaseless waiting. Both Kate Nachilobe and Shawn Vereschagin also remark that Moehn includes an interesting eighth-note figure in the piano line of the second song, “Trüber Tag,” which they interpret as the ticking of a clock as the protagonist continues to wait throughout the day.

Duo für Violine und Klavier / Duo for Violin and Piano (1936)

Performed by Hannah Lissel-DeCorby (violin) and Nicole Tremblay (piano)

I: Präludium, Allegro moderato

II: Andante quasi Adagio

III: Presto

Hannah Lissel-DeCorby and Nicole Tremblay record Duo für Violine und Klavier in Convocation Hall, University of Saskatchewan.

Photograph by Al Ramsay.

In the mid 1930s, Heinz Moehn’s compositional style backed away from the expressive extremes of his earlier compositions. In the Duo für Violine und Klavier, the harmonic language is quite chromatic, but firmly centred in the overall tonic key of F major. Violinist Hannah Lissel-DeCorby (who also contributed to the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra’s performance of Moehn’s Musik für Violine und Orchester) characterises Moehn’s overall style in this work as using “some dissonant sonorities, but putting it all together in a really lyrical and somewhat virtuosic manner.” Both Hannah Lissel-DeCorby and pianist Nicole Tremblay note the contrasting styles amongst the three movements of the piece. While the first movement evokes the American folk-like style of Copland, especially in the contrasting middle section, the second movement takes an ethereal turn, and the third movement walks the narrow borderline of exuberant playfulness and seething virtuosic energy. Throughout the piece, however, a consistent feature is the interaction between the violin and piano, which both take their turns playing supportive roles, but also build and interweave spectacularly at intense points in each movement.

Musik für Violine und Orchester / Music for Violin and Orchestra (1937)

Performed by the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra: Eric Paetkau, conductor; Timothy Chooi, violin.

Musik für Violine und Orchester was premiered by the Wiesbaden Symphony Orchestra on April 29th, 1938. Violinist Justus Ringelberg was the soloist, and the conductor, August Vogt, characterised Moehn as “belong[ing] among the strongest talents of the present generation” [“er zu den stärksten Begabungen der heutigen Generation gehört”] in a letter of support written on 28 March 1939. This piece, along with the others premiered in 1938, was acclaimed in national publications. The Zeitschrift für Musik remarked that Moehn was “deserving [of praise] in his serious, conscious individuality” for his recent large-scale works. In the 23 September 1938 issue of the Allgemeine Musikzeitung the reviewer responded more specifically to Moehn’s Musik für Violine und Orchester, stating that “in spite of the relatively great length, there exist no tedious, long-drawn-out passages, instead everywhere compositionally-meaningful necessities prevail.” Additionally, the reviewer noted that at the conclusion of the concert, “there was rich and enduring applause for the composer.”

This piece reflects Moehn’s turn in the mid- to late-1930s to larger-scale works. This shift to composing for larger ensembles and to tackling ambitious large-scale forms was related to both his growing prominence as a composer at this time, and his illness from 1936 to 1938, which forced him to give up employment but afforded him more time to compose. The work is in three movements and, like Moehn’s Duo für Violine und Klavier, it moves away from the composer’s earlier expressionism, perhaps turning towards the lightness and accessibility of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) at times, and to the extended melodies and emphasis on timbre of late Romanticism at others. Eric Paetkau, who conducted the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra in the North American premiere (and second worldwide performance) of the piece on 23 March 2019, notes the “slight jazz influence” that is audible in some of Moehn’s harmonies, mentioning how popular Ernst Krenek’s 1927 “jazz opera” Jonny spielt auf continued to be in the 1930s. The first movement combines touches of this harmonic influence with prominent showcasing of the winds and occasional playful pizzicati to create an overall lightness of tone, shaded at times with late Romantic chromaticism and long, intense solo violin lines. Violinist Timothy Chooi calls the second movement (featured in the video above) “the heart of the piece,” in which “time stands still.” He notes that Moehn’s lyricism is particularly evident in the solo violin’s long lines throughout this movement. The third movement evokes band music at times with its pronounced use of the winds and brass. Perhaps the dominant point of reference throughout this movement, however, is to film music. Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra first violinist (and University of Saskatchewan Bachelor of Music student) Hannah Lissel-DeCorby hears this connection in the sense of narrative and character Moehn creates, and Timothy Chooi notes stylistic similarities to Erich Korngold, who both composed “art music” and scored films such as Captain Blood (1935) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938).

“Am schwarzen Markt” / “On the Black Market” (1946)

Performance by Jayden Burrows (baritone) and Cynthia Wilson (piano)

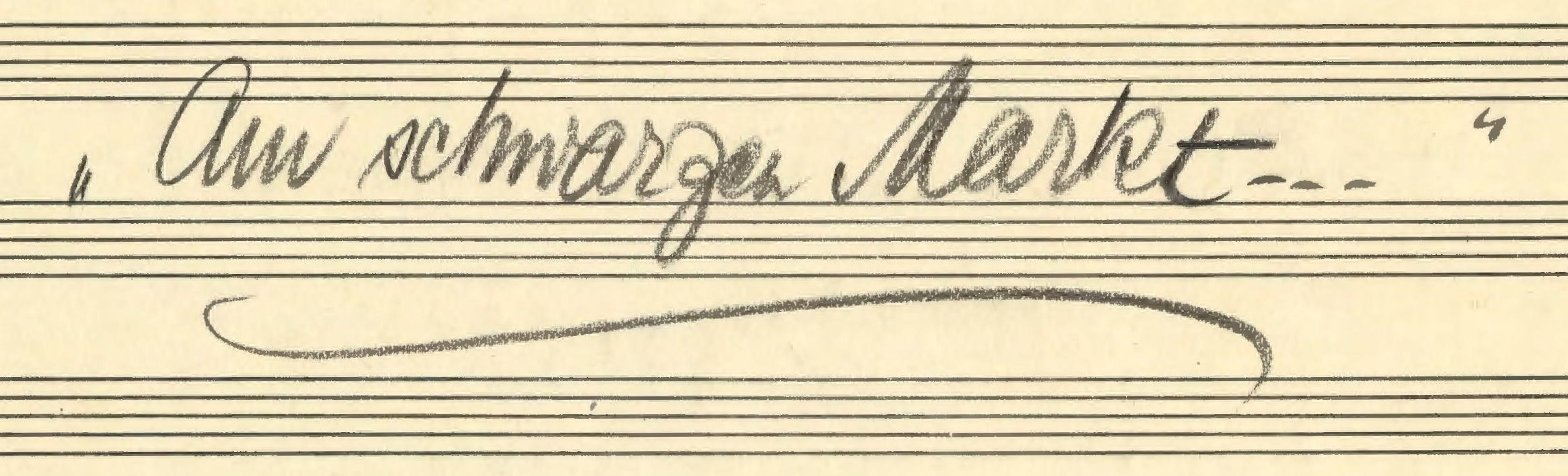

Detail from the title page of the manuscript

In 1946, Heinz Moehn composed one of his rare post-war works, a humorous cabaret-like song about the pleasures and perils of the black market, with lyrics by Oscar Albrecht. Baritone Jayden Burrows highlights some of the wares featured in the song: “they’re getting chocolate, American smokes like Lucky Strike, all the stuff you can’t get.” However, he notes that the song cautions shoppers to be wary – the overall message of the text is “look at how wonderful all the things you can get are, but if you break the law, you’re going to pay for it. That’s what you see in the final verse when […] the military police come and get you at the very end!” Musically, the song is a strong departure from Moehn’s other compositions. Though his previous works suggest a broad musical frame of reference, with traces of jazz influences, his output until this point was firmly within the “serious art music” tradition. In this song, the rollicking piano accompaniment, in particular, steps firmly into a popular idiom, even if the long and rapid list of desired goods presents a considerable technical challenge for the singer.

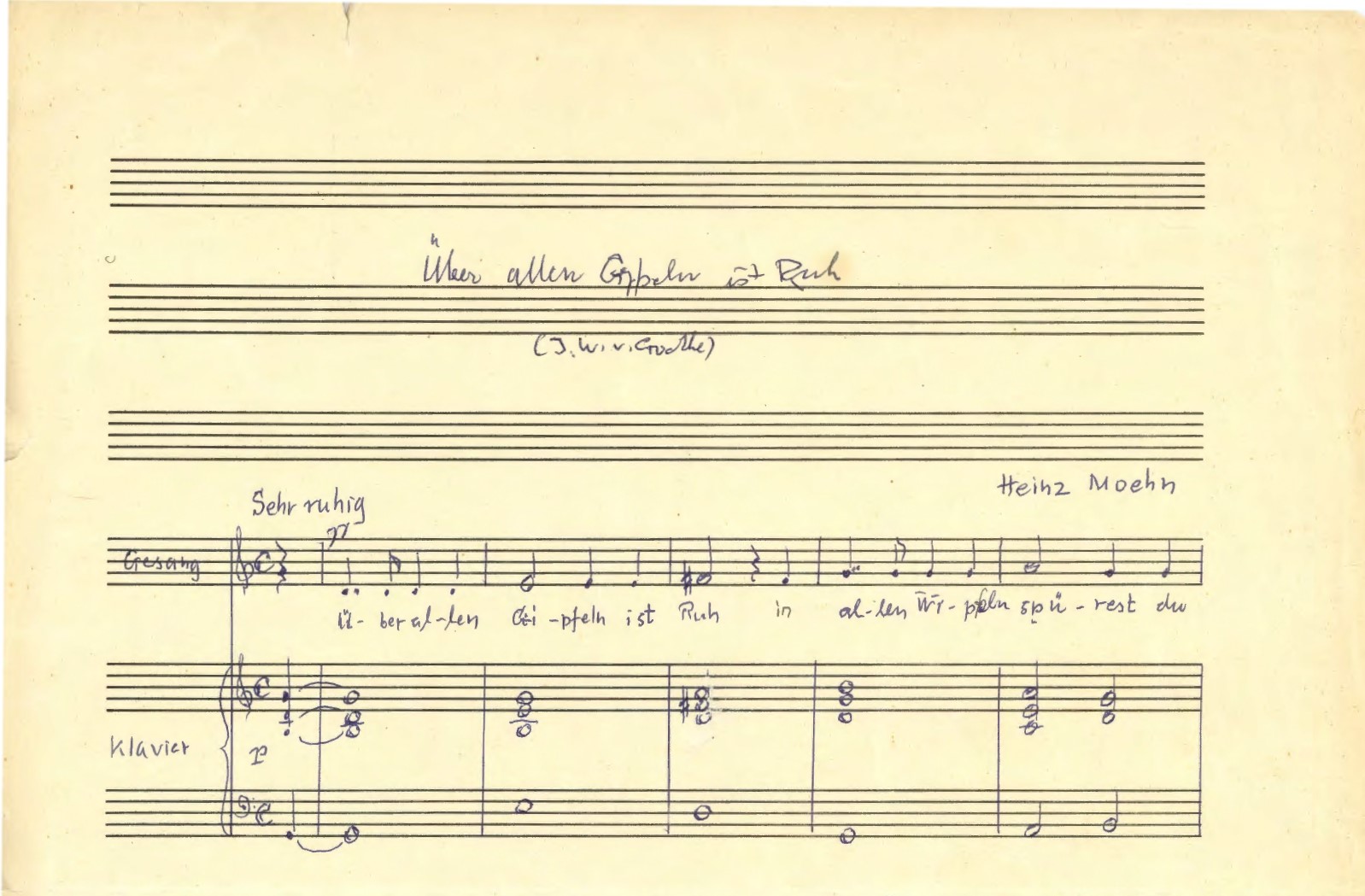

“Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh” / “Over All the Peaks is Peace” (1991)

Performed by Angela Gjurichanin (soprano) and Cynthia Wilson (piano)

In 1927, Goethe’s iconic poem “Wandrers Nachtlied II” (also known as “Ein Gleiches” and “Über allen Gipfeln”), inspired Heinz Moehn to create one of his first Lieder, but he left the piece incomplete. The poem is one of the most celebrated texts of German literature, and was set by a multitude of composers, including Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, and Franz Liszt. Moehn returned to the poem to create his last extant composition, dated 10 July 1991. This later setting is entirely different from his early attempt, and takes a very spare approach in both the voice and piano parts. Both soprano Angela Gjurichanin and pianist Cynthia Wilson remark upon the technical simplicity of the song, which requires both musicians to be united in their interpretation. The poem concludes with the lines “Warte nur, balde / Ruhest du auch” (“Just wait, soon / You, too, will rest”), and Angela Gjurichanin emphasises that her interpretation aims to express a sense of peacefulness in the face of death.

Detail from the manuscript

Sources:

Meißner, Richard. “Wiesbaden.” Allgemeine Musikzeitung 65 (23 September 1938): 570.

Vogt, August.

“Wiesbaden.” Zeitschrift für Musik 105 (December 1938): 1396-97.